There are two common themes in modern Bible scholarship that both underlie and undermine current trends in Biblical theology. Both are related to simple questions that sharply divide conversations over the past couple of centuries. When dealt with in both theological and philosophical arenas, I would contend the most important to how we approach God and His Word.

The first question is this:

DO WE TRULY POSSESS THE WORD OF GOD?

The quick response would likely be, “Of course we do! I have a Bible right here in my hand!” On the surface this question seems that simple, but it is far from it as we dissect what it means to have the Word of God. What seems like a clear answer becomes far murkier the more most people discuss this.

The most common logic of today is ambiguous, claiming both that we do and we do not have the Word of God. One common argument made is the Bible was perfect in its original text, but that we have lost this perfect text over centuries of copying the text. The website Got Questions (which I do find to be very helpful in most cases) asks “Is the original Bible still in existence?” and answers: “The answer to this question is both ‘no’ and ‘yes.’ In the strictest sense, no, the original documents that comprise the 66 books of the Bible—sometimes called the ‘autographs’—are not in the possession of any organization.” After a lengthy discussion of how the text came to be and how it was passed down to today, the article concludes:

“In summary, while no one today possesses the original autographs, we do have many extant copies, and the work of biblical historians via the science of textual criticism gives us great confidence that today’s Bible is an accurate reflection of the original writers’ work. As an analogy, if the original and preserved unit of measure known as a ‘yard’ was lost in a fire in its holding place in Washington, D.C., there is little doubt that that measurement could be replaced with full assurance through all the exact copies of it that exist elsewhere. The same is true of God’s Word.“

This line of logic essentially flows like this:

- God gave His perfect and complete Word to the original authors who faithfully and perfectly recorded the exact words.

- These original records were copied before they were lost to history.

- Errors and mistakes were introduced into the text through the process of copying and distribution by fallible humans.

- Therefore, we do not and cannot possess a perfect and complete record of God’s Word.

- The solution to this problem is to try to recreate the lost record through textual criticism, thus providing us with our best guess at what the original text contained.

This logic is in substance and application Theseus’s Paradox. It holds that both the original, “lost” text is the Word of God. It also holds that the modern reconstruction of the text is the same Word of God. It also adds an interesting variation in that is ongoing doubt as to what constituted the original form, so every effort to reconstruct the original may actually move it further from the original form.

The origins of this logic did not come from faith, but from applications of a secular science of textual criticism. In the late Middle Ages in Europe, there was a revival of interest in classical works of antiquity. This focused primarily on Greek and Latin texts that were not Christian. This developing science was eventually applied to the Scriptures, which The Encyclopedia Britannica states:

“From about 1350, however, a change in attitude is evident, particularly in the West. What is often called the revival of learning was in reality a practical movement to enlist the heritage of classical antiquity in the service of the new Christian humanism. In order to make them usable (i.e., readable), texts were corrected freely and often arbitrarily by scholars, copyists, and readers (the three categories being in fact hardly distinguishable).“

When dealing with multiple texts that contained different variant readings, certain rules were developed to help guide the critic. These are based on assumptions and continue to guide thought today. Some of these include:

- Older texts are more reliable than more recent texts.

- Lectio difficilior potior – “the more difficult reading is the stronger”

- Lectio brevior potior – “the shorter reading is stronger”

The underlying problem with textual criticism is that it cannot be concluded. It claims to attempt to reconstruct the original text, but it is driven by the whims of scholarship and bias. Even though this practice has been in place for multiple centuries, it is no nearer it goal than when it began.

Two battle primary battle lines have developed. The first is around the Greek Textus Receptus and the Hebrew Masoretic Text, the second around the various critical texts that have been produced. The Textus Receptus and Masoretic Text represent an accepted standard, which the critical texts attempt to create a new standard. The debate around these texts is complex and not nearly as simple as I wish it were, and I am not even touching the debates about translation mechanics here!

But I return to my initial question: CAN WE TRULY POSSESS THE WORD OF GOD? One side (proponents of the Textus Receptus and Masoretic Text) profess that we can and do. The other side (proponents of textual criticism and critical texts) claim that we cannot. When you reduce the debate to its elementary essence, that is what you are left with.

My belief is that it really comes down to faith. I can build logical arguments for both sides of the debate, but Christianity is built on faith and not logic. Faith is not always logical. Faith is often found in trusting the unknowable.

Do we really believe what the Bible says? Do we believe that God is omnipotent, omniscient, and omnipresent? Do we believe that He created all things? Do we believe He sent His Son to be die for our sins and that He rose again?

If we believe these things, do we also believe that God meant what He said about His Word being preserved for all generations (Psalm 119:89, Isaiah 40:8, Matthew 5:18, Matthew 24:35)? Do we believe that the God who gives us life and holds our salvation in His unfailing grace cannot also preserve His word faithfully through the ages? If God can keep you saved for eternity, can He not also keep His Word pure?

I am alarmed at the number of Christians who attest in faith that God can do anything yet so readily deny that He can preserve His Word. I grow tired of every time someone addresses the reliability of the Scripture that they feel like the must add a proviso that it was only pure in its original manuscripts which we no longer possess.

Friends, we can have a faith that is founded on God’s revelation of truth that His Word may be preserved pure for us today. That is not even a blind faith, as logical arguments can be made to support it. I am convinced that modern Christianity needs a return viewing the Bible as “Thus saith the Lord” and not continually asking “Yea, hath God said?” I am convinced that the confusion brought about by textual criticism in the past two hundred years is a symptom of a grievous error brought about by doubting God. Voices have continuously implicitly or explicitly stated that you cannot have God’s true Word, and now we marvel why so many do not view the Bible as authoritative.

I am going to take this one step further before moving on. I am becoming more and more convinced that this is the underlying debate about using the KJV. There is a direct correlation between trusting the KJV and rejecting the tenets of higher criticism that has developed since 1611. There is also a vast difference in how KJV users typically teach and preach because they present the text as the Word of God without adding qualifying statements undermining its authority.

If we can have truly possess the word of God, there there is one more question to address:

CAN WE TRULY UNDERSTAND THE WORD OF GOD?

Not only does modern Christianity doubt that we have the Word of God, but also that we cannot understand what it says. I am not here talking about the absurd arguments about archaic language of the KJV. I am talking the many new methods of Biblical interpretation that have arisen recently that seem to hold that you cannot really understand the truth of God’s Word.

One common method that does this is labeling portions of Scripture as figurative or allegorical. This is often used to attempt to reconcile the opening chapters of Genesis with modern theories of evolution. They will claim that God did not literally create the world in six days and that Adam and Eve may not have been literally the first humans. A corollary to this that I am seeing more and more often is labeling prophetic books (especially Revelation) as apocalyptic literature.

Something else that is growing in popularity is the idea that we must view the contents of Scripture through the culture and understanding of its original cultural setting. On the surface, I want to agree with this approach but the more I dig into it the less comfortable I become with it. It is intrinsically faulty because it is based on our own assumptions of the mindset and knowledge of people thousands of years before us and thousands of miles away from us. I feel that books like Misreading Scripture with Western Eyes are both helpful and hurtful. This is very tricky ground to traverse and its most logical conclusion almost has to be that we just cannot properly comprehend the Bible because our culture is so vastly different that it was in Bible times. But then again, we may counter that the essence of humanity is largely the same today as it always has been.

Another quite opposite tendency that is common today is the attempt to read modern thought and theory into Scripture. We see this in feminist theology and liberation theology. There are so many other absurd examples of this, including cannabis and UFOs. There are other less extreme examples, such as reading modern Western music theory into the music of the ancient Jews (I am putting together some material on this subject).

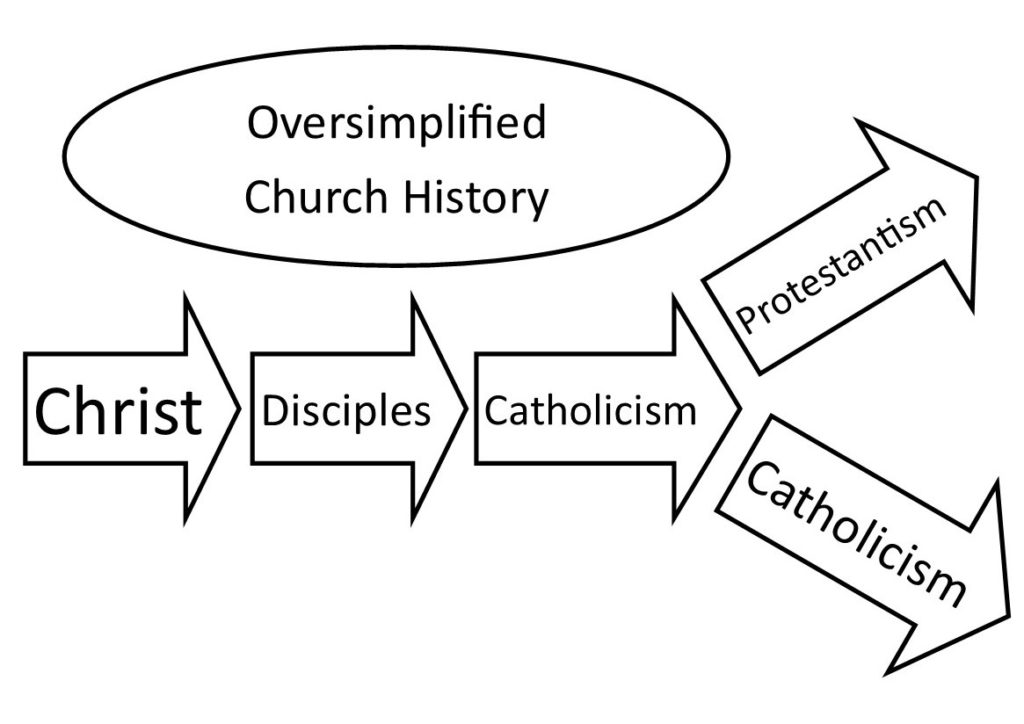

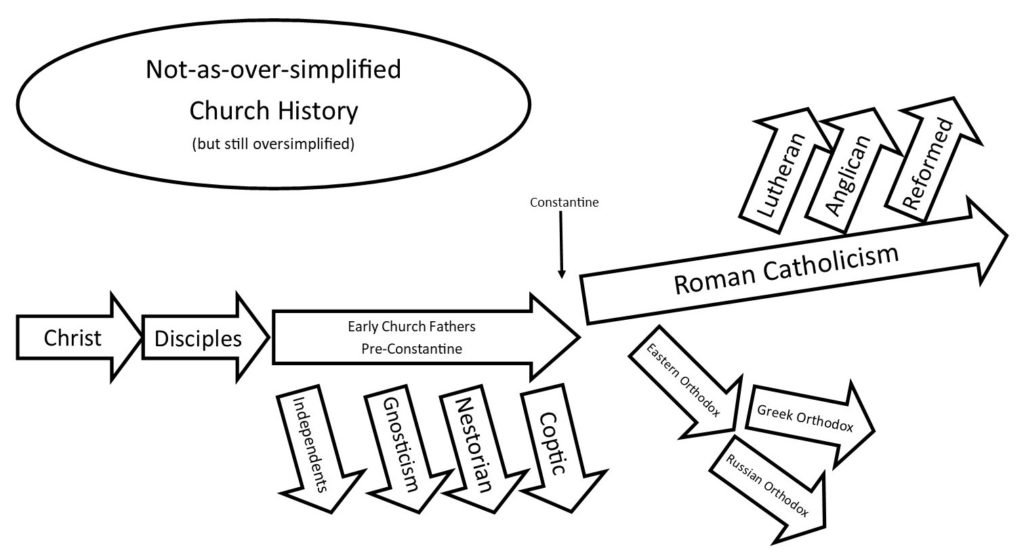

What these approaches and others like them do is create a break between modern Christianity and historic, orthodox Christianity. It exhibits chronological snobbery with a profound arrogance that assumes no one better understood the truths of Scripture before modern scholarship. There are so many examples of this, such as the so-called New Perspective on Paul, with more examples produced daily. I wish more people would stop and think that if you find something in the Bible no one else has ever found, then there is probably a good reason no one else has ever seen it!

Another problem I see that stems from this hubris is the assumption that the common person is helpless to understand Scripture on their own. This is one impetus behind the constant revisions and translations of Scripture, to try to keep the Bible “relevant” so that modern readers can comprehend it. It is also seen in the idea that you cannot truly know the Bible until you can read and understand it in the original Greek and Hebrew.

Friends, you do not need a master’s degree in theology to understand God’s Word. Christ Himself spoke to the common people and Paul wrote to the average Christian. David wrote songs that were sung by congregations of common people. Yes, there are infinite depths to the truth of Scripture, but there essential truths are so simple that a child may follow them.

I am afraid that academia has convinced us that we must be one of them to have true faith and understanding. This is counter to the clear teachings of Scripture, which entrusted much of the propagation of truth to common people (Deuteronomy 6:1-9). They have also convinced us that unless you are of their number or at least have their blessing that you cannot be successful in ministry. They have the same prejudice as the Jewish leaders in Acts 4:13.

Education is important, but it is far from the most important thing a Christians needs. We need faith to believe and trust in God. We need faithfulness to serve God and observe His commands. His truth is sufficient. We can grasp it, absorb it, and practice it. We can be honest in our lack of understanding in difficult areas, but we must be faithful to the truth we know.